Genetics are the engine of the livestock industry, according to Animal Genetics and Breeding Unit director Steve Miller.

An engine which takes information producers collect - being pedigrees, phenotypes and genotypes - and turns them into information that can be used to make selection decisions.

With the development of genomic selection, Mr Miller told the Leading Breeder conference in Bendigo in March, the genetic engine has gone from running on steam to internal combustion.

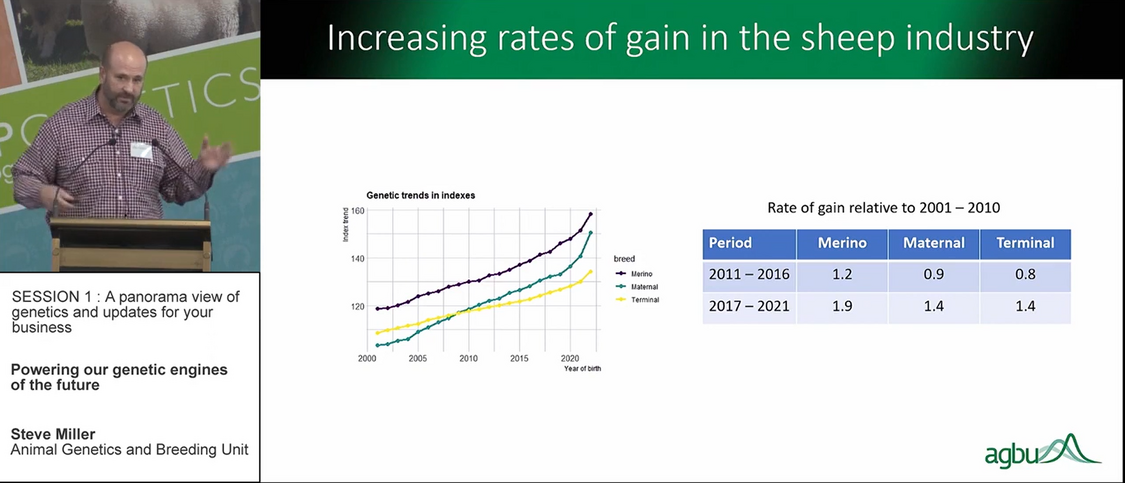

More literally, the rate of genetic gain has gone from 0.8 in 2016, to 1.4 in 2021.

“When you got full single step analysis…you now have the most up to date internal combustion engine available to you as breeders, it is up to you to get out there and use it and make the most of it,” Mr Miller said.

”One of the big advantages of genomic testing is you get a much better pedigree…that has been a big plus for genetic progress.

“New breeding objectives, and getting all the economic important traits, including some of these hard to measure traits like reproduction and eating quality all into your index is also important.

While genomics has contributed to the increased rate of genetic gain, Mr Miller is keen to point out it isn’t the only factor.

“You can’t fuel the genomic engine…without the data,” he said.

“We don’t get this prediction accuracy from nowhere, it has got to come from somewhere.”

Much like electric cars, the power still has to come from somewhere.

And that power is data that has come from the vast number of sheep that have been measured in the past, with the development of resource flocks crucial to this.

Mr Miller said having that genotype database is now allowing the industry to target the measurement of commercial animals, as well as hard to measure traits such as eating quality.

The American Angus Association is the largest beef breed association in the world and they register 50 per cent more animals than the entirety of Breedplan across all breeds in Australia.

Mr Miller previously worked at that Association, and said while the organisation now has over one million genotypes recorded, when he left the organisation breeders had stopped recording data as consistently, which was a problem within itself.

“At one stage they were bringing in 120,000 ultrasound records per year for carcass traits, they are now down under 80,000, that’s quite a drop - why would that be?

“They can actually get a very accurate breeding value now just with genomics, and if they phenotype the animals on top of that the accuracy really doesn’t go up hardly at all - so why would you go through the expense and the risk…to do the phenotyping?

“So how do we keep the phenotyping going in light of really accurate genomic predictions?”

Mr Miller said while this is a good position to be in, not a problem, with genomic breeding values being so accurate, there were lessons for the Australian sheep industry.

Being that phenotype is still king, and we must continue to demonstrate why to the data collectors.

So what will power the genetic engines of the future?

A system that combines pedigree, phenotype and genotype to provide the best selection information.

“The future is going to be based on more powerful information, more phenotypes, more genotypes…more traits, which means for the industry and you the breeders more work, which means for us more research, and we need to develop a system that can handle all that, and that is a little bit us taking the FJ Holden and making it into the Hilux,” Mr Miller said.