Carbon Neutral by 2030 (CN30) is an ambitious target for the Australian red meat and livestock industry to achieve net zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030.

This means that, by 2030, the industry aims to make no net release of GHG emissions into the atmosphere.

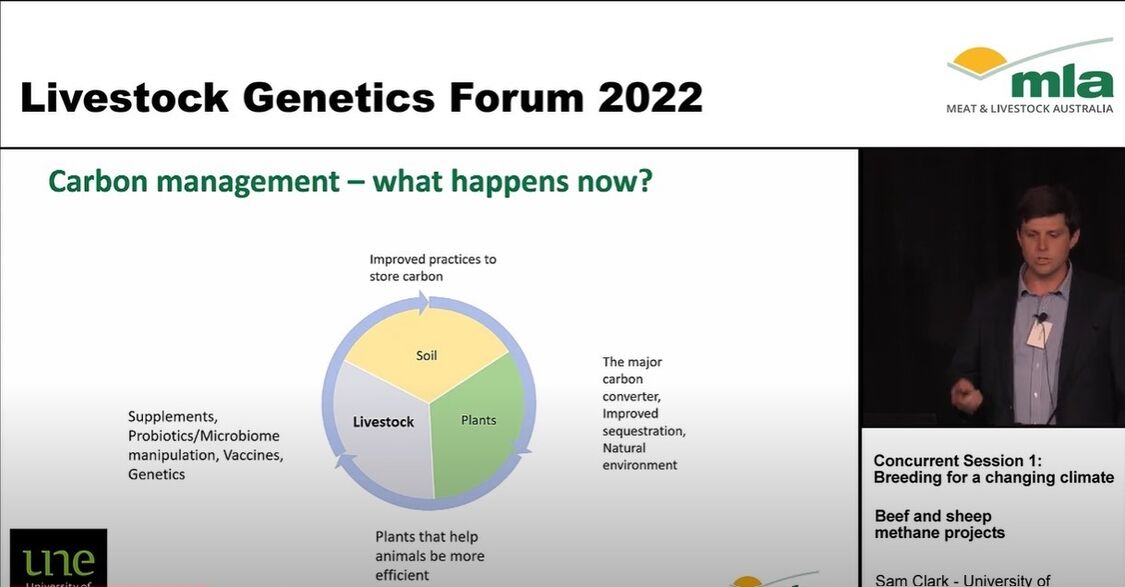

Speaking at the 2022 Livestock Genetics Forum in Adelaide earlier in the year, University of New England’s Sam Clark discussed two projects that are using genetics to work towards this goal - the Genetic improvement pipeline to reduce methane and improve productivity in the Australian beef industry and Selection for more methane efficient sheep.

“Not all animals were created equally - some animals will produce more or less methane per day,” Mr Clark said.

“What our role in genetics is to think how much of this variation is genetic?”

Mr Clark told attendees that the National Livestock Methane Project, which concluded in 2015, found the heritability of methane production was 0.31, which is considered by industry to be moderately heritable

“We can make good changes to methane outputs using a trait that has heritability of .3”,” Mr Clark added.

“How do we find more efficient animals? In animal breeding it is a pretty simple answer - measure, measure and measure some more.

“To find animals that have that low methane production, we have to actually measure them.”

Methane projects being undertaken by a number of industry bodies, including the NSW Department of Primary Industries and Meat and Livestock Australia, are building reference populations of sheep to allow researchers to understand what animals produce.

Mr Clark said the two current projects were aiming towards the same thing - developing a pipeline for collection of emission data, form a reference population for genomic selection for reduced GHG emissions, and create EBVs (estimated breeding values) for emission traits for selection of low emitters.

“The overall goal is to reduce individual animal methane emissions while improving overall productivity,” Mr Clark said.

To measure sheep emissions, a portable accumulation chamber is being used.

“It is essentially a little plastic box that will travel around between farms…we put an animal inside the accumulation chambers to measure their outputs, and we also measure feed intake…feed intake could be a very useful measure of how efficient that production system is,” Mr Clark said.

“The project already includes measurements for reproduction traits, wool traits, weight traits, many of the key breeding traits already selected for.

“So it is using the existing pipeline of Sheep Genetics and adding two more traits, methane and feed intake.”

This year there will be 5000 resource flock lambs, and 5000 breeder and resource flock ewes recorded for methane output, all of which will be genotyped.

Once the data has been collected industry will be able to better determine what can be achieved through genetics, and adapt the importance of methane emissions in breeding value indexes accordingly.

By making a 1 per cent reduction in methane outputs in the flock each year through genetics, it will equate to 5 megatonnes over 30 years.

“So if we don’t add methane (reduction) into our production system and don’t record it, we have a net change of 10 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent being saved from our production system.”

Mr Clark said while there were supplements which improved methane outputs, they would always have to be paid for, while genetics doesn’t.

“Genetic change is permanent, cumulative and long lasting - if we stick to a breeding objective and people remain disciplined about making that genetic change, long term permanent change is possible,” he said.

“Reducing individual animal methane emissions whilst improving overall production efficiency is possible with genetics, and it is an accumulative long lasting process, and the sooner we start the better because 1 per cent a year adds up over time.”