New Zealand is making significant gains when it comes to selecting sheep that produce less methane.

Nearly half of all total greenhouse gas emissions in New Zealand comes from livestock, with 18 per cent of that from sheep, which is it’s an important part of Beef & Lamb NZ’s focus.

General manager of Genetics Dan Brier told the Global Sheep Forum recently that New Zealand has a target of lowering methane 10 per cent by 2030.

And New Zealand had the foresight to see methane was going to be a challenge for the industry in the future, beginning to research solutions back in 2003.

“The key goal of mitigation research is to try and separate the link between the amount of pasture an animal eats from the amount of methane that animal produces,” he said.

“So for every kilogram of pasture that your sheep eats in NZ it will produce 21 grams of methane - if you grow it faster it will produce more methane, but slower and it will still be 21 grams.

“Our goal is to break the link, to make it 18 or 16 grams of methane produced for every kilo of pasture taken in.”

How to do this? Collaborative industry research in New Zealand has focussed on four main research areas - low greenhouse gas feeds, vaccines, inhibitors, and low methane animal genetics.

Mr Brier said so far, genetic selection offered the biggest opportunity, as not only could it mean less emissions, but also more productive animals.

“Genetics selection for low methane is a bit of a holy grail because genetics is like rust, but in a good way - it never sleeps,” he said.

“If you breed an animal and make the right breeding decisions, you get payback for that for generations and generations.

For instance our industry in NZ is now essentially 30 per cent more efficient now than it was 30 years ago and that is largely driven by genetics and feed.”

Genetics is also set and forget, rather than requiring changes to management practices, Mr Brier added.

AgResearch NZ began measuring methane emissions from one of their well documented research flocks, and by mating high emitters with high emitters and low emitters with low emitters, established it was a heritable trait.

Mr Brier said the heritability was abou 0.2.

“(That is ) similar heritability to that of weaning weight… a lot of our farmers spend a lot of time trying to select for faster growing lambs, so this (methane emissions) is about the same heritability and it is about twice the reproductive traits which our farmers also select for,” he said.

They began taking measurements 11 years ago, and initially found there was a 4 per cent differentiation across the flock.

This has now grown to 11 per cent, and they have found no adverse genetic impacts - meaning it doesn’t negatively correlate with any other traits.

Research has expanded to a number of flocks across the country, with the measurement tools heading out to farms for the past three years.

Mr Brier said they were now at the stage of providing breeding values for the trait.

“Breeding value means that we have done enough real tests, collected enough traits, that we can begin to estimate how their relatives will behave,” he said.

“We’ve got up to 10,000 tests and that is a magic number - we know the accuracy is good enough that we can move from flock level measurement to industry level measurement.”

Any sheep producer already doing genetic evaluation can tap into methane measurements by registering via methanebv.co.nz, and a trailer with the technology visits them on-farm.

It costs $30/sheep and each producer needs to do 80-120 sheep each, but it is part-funded by Beef & Sheep NZ.

This year, they intend on taking a further 5000 measurements and using those to estimate how the methane genetics are changing across the industry’s entire flock.

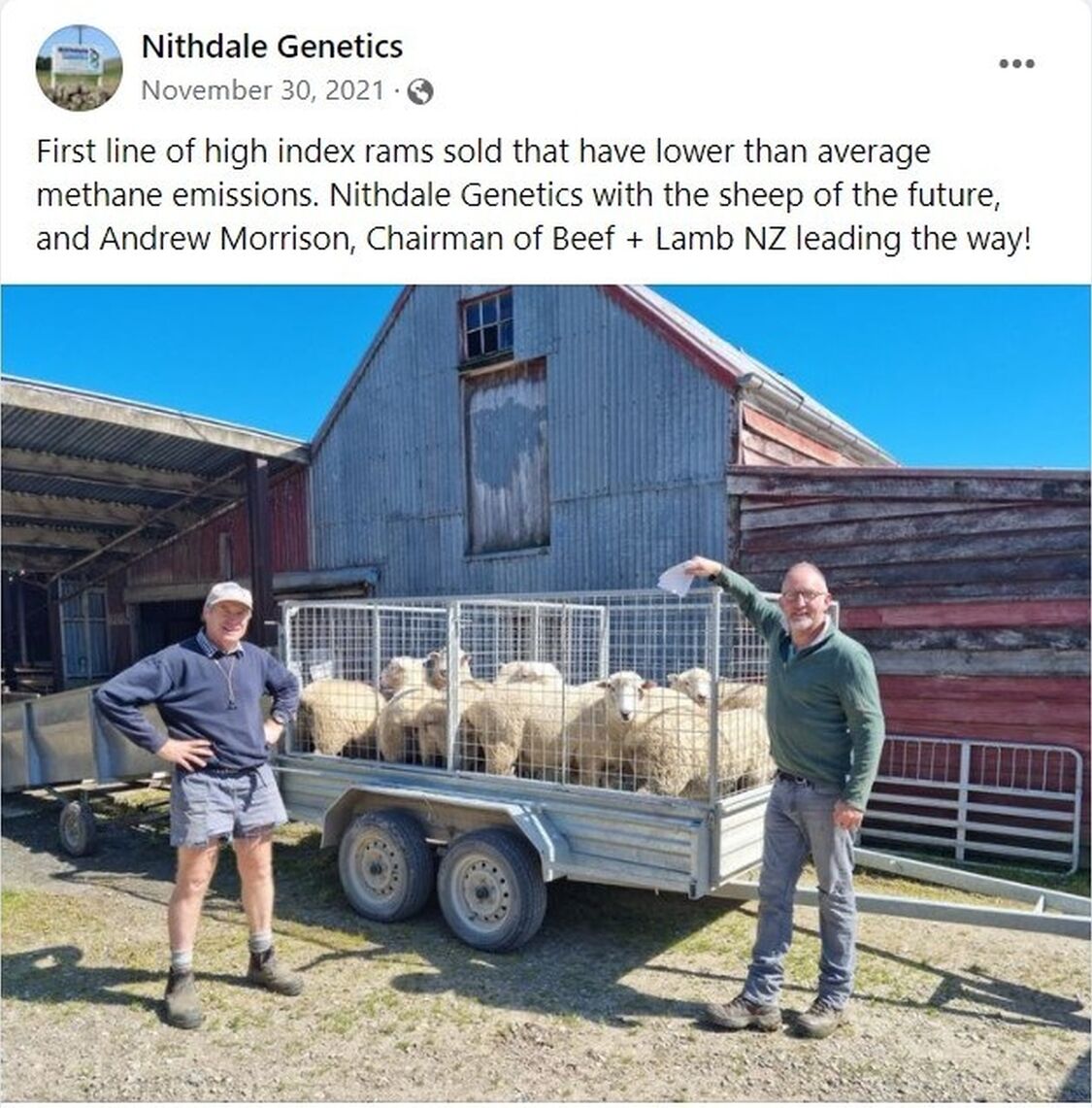

Mr Brier told the online forum that Nithdale Genetics, a stud at Gore, NZ, have sold the first rams in the country with “lower than average methane emissions”.

And the next step for Beef & Lamb NZ Genetics was creating an index which includes methane.

“Genetics is as close as we’ve got to something that farmers can do to actually reduce their methane without having to just reduce stock, or rely on sequestration,” Mr Brier said.